Implications of Reconstruction:

Where Exactly was the Temple on the Temple Mount?

With a mostly intact Temple Mount alongside descriptions of the Temple from both scripture and contemporaneous literature/historiography, one would think scholars could be able to determine the location of the Inner Temple. However, the precise location of the Temple on the Temple Mount remains one of the most hotly debated subjects among scholars, and none of the proposed locations is without problems. This section reviews three scholars’ proposals for the location of the Inner Temple. Common assumptions shaping theories of the Temple’s location include:

- Each time the Temple was reconstructed, it maintained the same location and footprint as the original (First) Temple built under King Solomon

- The eastern wall of the Temple Mount could not move further east because it abutted the Kidron Valley. Therefore the angle and placement of that wall predated Herod’s Temple Mount.

- Both the floor of the sanctuary (Holy of Holies) and the altar had exposed bedrock.

- The Rock under the Dome of the Rock is currently the highest elevation of exposed bedrock on the Mount and therefore could be the location of the Holy of Holies or the altar

Proposal 1: Leen Ritmeyer

(See: L. Ritmeyer. The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Jerusalem, Israel: Carta, 2006.)

Leen Ritmeyer is an archaeological architect who participated in several excavations around the base on the Temple Mount. He spent many years examining the question of where exactly the Temple once stood. He believes the Rock is the site of the Holy of Holies. In fact, after close examination of the Rock, he believes that he identified the trench that would have held one of the walls of the sanctuary, and even an indented rectangle in the Rock where he believes the Ark of the Covenant stood in the First Temple period.

In order for the Rock to be the floor of the Holy of Holies, the whole Inner Temple must be lower than many scholars and sources suggest. For example, Ritmeyer is unique in placing the Court of the Women (the eastern court of the Inner Temple) at the same level as the surface of the Temple Mount (other scholars place it 6 cubits higher). However, he appears to rely on the a priori assumption that the Rock is the foundation of the Holy of Holies, rather than engaging in unbiased analysis to determine if the Rock could be that foundation. For example, he writes that it would be “quite impossible” to have stairs leading to the Court of the Women, “as it would put the floor of the Sanctuary 10 feet 4 inches (3.15 m) above the Rock.” (The Quest, p. 362). For a similar reason, Ritmeyer contends that the elevation from the Court of the Women to the Court of the Priests was 6 cubits rather than 10. Consequently, Ritmeyer places the floor of the sanctuary a full 10 cubits (5.24 meters) lower than most other scholars.

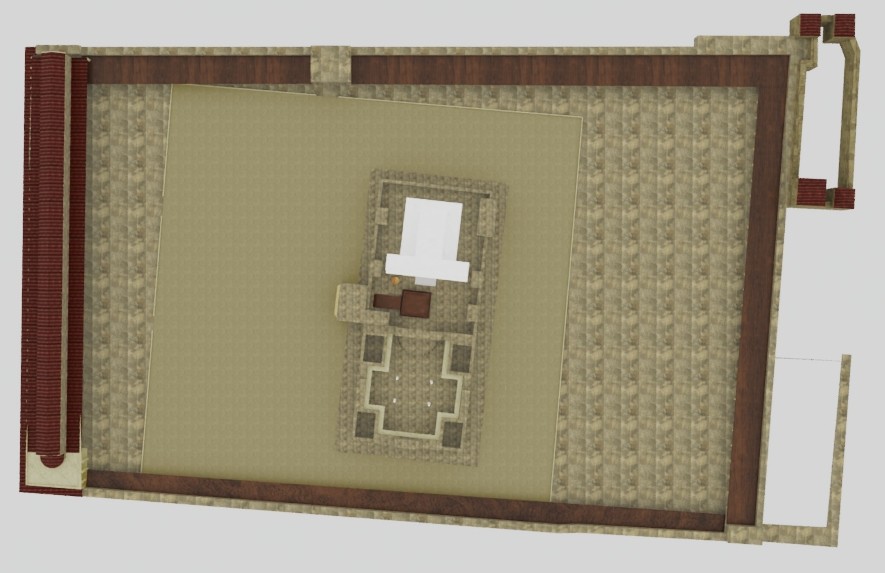

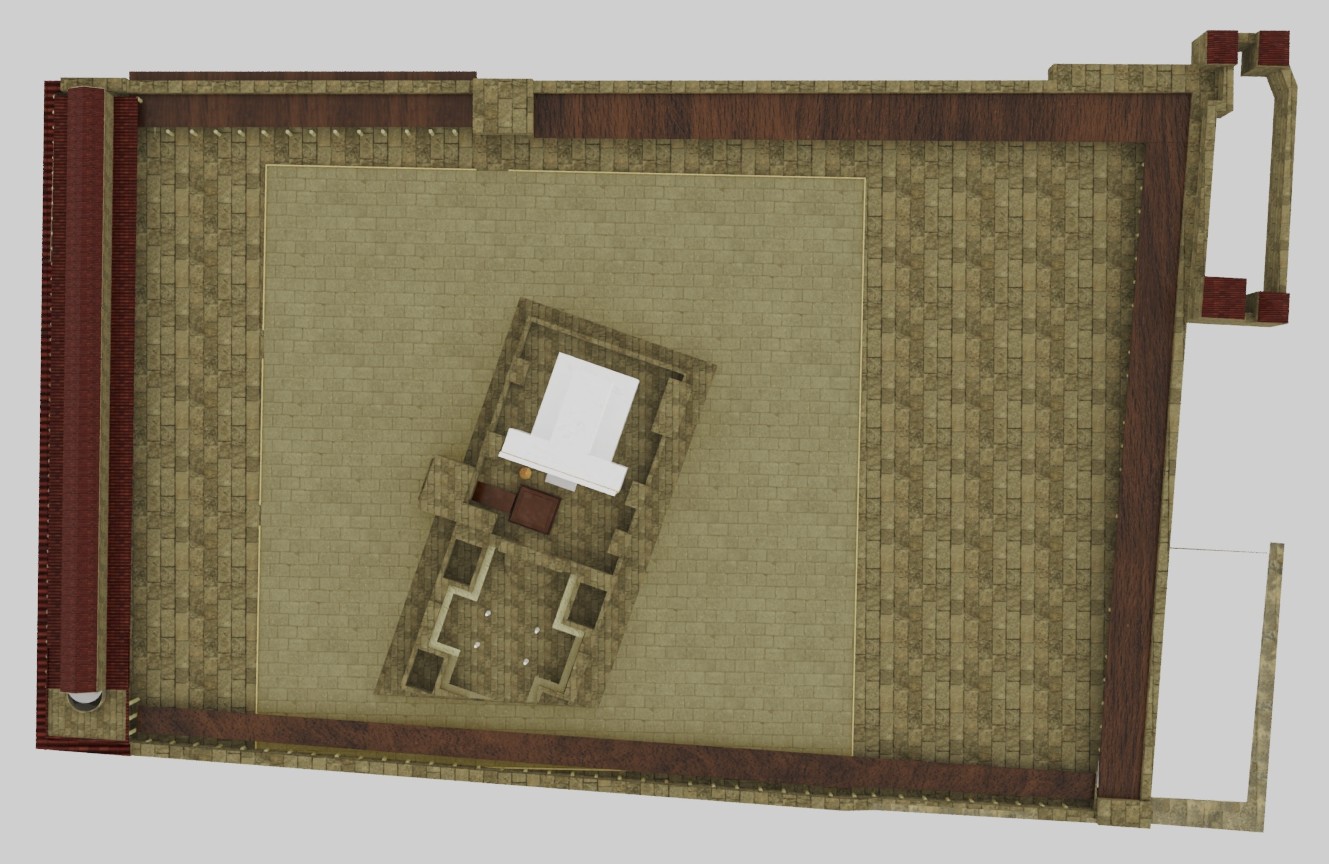

On the Temple Mount itself, Ritmeyer aligns the temple perpendicular to the eastern wall of the Temple Mount, as this wall predates the Herodian expansion of the Mount. He also locates it within a 500-cubit-square area he believes to have been the original Temple Mount, based on an examination of the foundation masonry to determine stages of expansion. In the expanded, Herodian Temple, this area assumed to be the original Temple Mount was referred to as the Court of the Jews, and the outermost of the courts considered sacred. For Ritmeyer, the location of the Temple within that square is determined by the location of the Rock rather than measurements found in Middot.

Proposal 2: Joseph Patrich

(See: Patrich. “The Location of the Second Temple and the Layout of its Courts, Gates, and Chambers: A New Proposal.” In Unearthing Jerusalem: 150 Years of A

Archaeological Research in the Holy City, edited by Katharina Galor and Gideon Avni, 205-229. University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns, 2011.)

In direct contrast to Ritmeyer (above) and Reznick (below), Patrich argues that the Rock currently in the Dome of the Rock cannot be the bedrock within the Holy of Holies or the bedrock under the altar. He estimates that the Rock would have been about 1.5 m under the Court of the Priests (the level of the altar) and an addition 6 cubits (3.1 m) below the sanctuary. Instead, Patrich bases his hypothesis regarding the location of the Inner Temple on the layout of cisterns beneath the surface of the Temple Mount.

Cisterns were crucial for cultic practice inside the Temple: priests were required to perform specific cleansing rituals, and animal sacrifices necessitated frequent cleaning of the altar and surrounding areas. Water wheels were used to access the water in the subterranean cisterns, and drains were strategically placed near the base of the altar to facilitate removal of blood and water. Based on close reading of Mishnah tractates Tamid, Yoma, and Middot, Patrich reasons that the cistern referred to as Cistern 5 marks the most likely location of the Temple. It the Temple was placed along the longest arm of this cistern, its various arms would reach each of the areas where water was used. The cistern also contained enough water to flush debris from the entire upper Temple courts.

Patrich’s placement of the Temple does not align with any of the walls of the Temple Mount; however, he argues no walls existed when the First Temple was built, and his proposed alignment is perpendicular to the natural contour of the mountain, making it feasible because each rebuilding of the Temple used the same footprint.

One area where Patrich agrees with Ritmeyer is in the location of the 500 cubit square area. Using Patrich’s placement of the Temple and Ritmeyer’s placement of the square, Patrich notes that diagonals of the square intersect at the entrance to the Temple proper. He takes this as an indication that the earlier Temple Mount represented by that square was built to fit the location of the Temple.

One area where Patrich agrees with Ritmeyer is in the location of the 500 cubit square area. Using Patrich’s placement of the Temple and Ritmeyer’s placement of the square, Patrich notes that diagonals of the square intersect at the entrance to the Temple proper. He takes this as an indication that the earlier Temple Mount represented by that square was built to fit the location of the Temple.

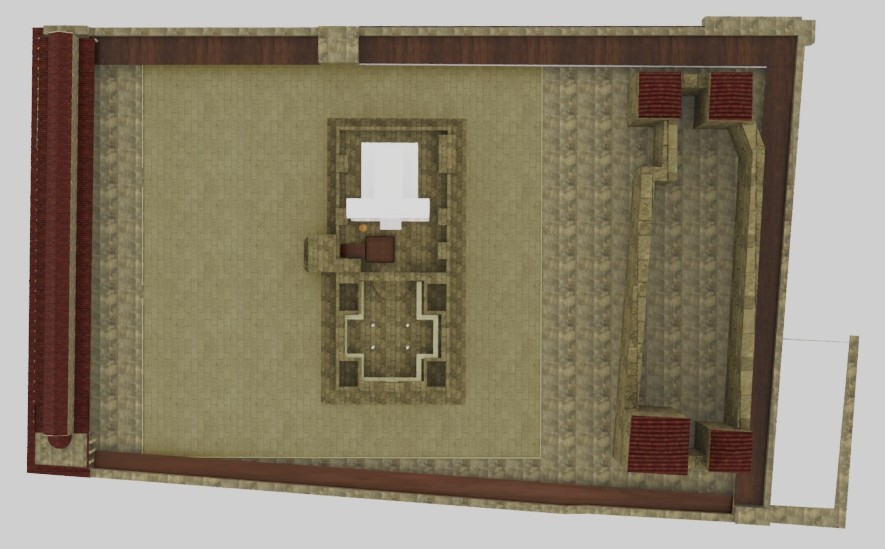

Patrich acknowledges that his placement of the Temple would leave limited space between the entrance of the Court of the Women and the eastern wall of the Temple Mount. While a rectangular court could fit, albeit tightly in the available space, Patrich proposes that the Court of the Women was actually trapezoidal, making its eastern wall parallel to the eastern wall of the Temple Mount.

Proposal 3: Rabbi Leibel Reznick

(See: Reznick. The Holy Temple Revisited. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1990.)

Reznik’s theory draws heavily on the Mishnah and Talmudic commentaries on it, although he incorporates Jospehus and the current layout of the Temple Mount in his analysis. Because the Holy of Holies and the altar were both situated on bedrock, Reznik makes the a priori assumption that the Rock must be the site of either one or the other. He tests out both possibilities but concludes that it is most likely the site of the altar.

His argument rests on a few key considerations. First, like Patrich, he calls attention to subterranean pipes and channels, but emphasizes drainage rather than cisterns. Specifically, he notes that 19th century investigations discovered that there is a hole in the Rock that leads to a chamber beneath the Rock, and another hole beneath the first that connects to a drain into the Kidron Valley. Reznick hypothesizes that these holes are the location of the drains along the foundation of the altar.

Second, he speculates about the period in 130-133 C.E. when Simon Bar Kokhba reclaimed Jerusalem from the Romans. Some of the rabbis thought that he might be the messiah and, according to Mishnah tractate Taanis, Bar Kokhba proclaimed himself both king and messiah. One expectation of the Jewish Messiah is that they will rebuild the Temple following the description recorded in Ezekiel, which differs significantly from the First and Second Temples. Ezekiel’s Temple is almost square, with concentric courts surrounding a central altar. Reznick hypothesizes that Bar Kokhba actually began building the Messianic Temple, and that the current raised platform surrounding the Dome of the Rock was originally Bar Kokhba’s Court of the Women. Reznick notes that the dimensions of this court, per Ezekiel, are 346 cubits by 340 cubits. If a cubit equals 19.07 inches, these would be the exact dimensions of the current platform. The location of the Rock unfrt the Dome of the Rock therefore corresponds to the location of the altar in the Messianic Temple. Although Reznick does not state this explicitly, he likely assumes that those who returned to Jerusalem with Bar Kokhba a mere 60 years after the destruction of the Temple would have been able to identify the site of the Second Temple altar.

To determine where the Temple was situated on the 500 cubit square, Reznick relies on the Talmudic commentary of Shiltai HaGiborim, who lived in the 16th century C.E. (1500 years after the Temmple’s destruction). Based on this commentary, Reznick places the Temple 63 cubits from the western edge of the square, 100 cubits from the northern edge, 250 cubits from the eastern edge, and 265 cubits from the southern edge.

Analysis

Ritmeyer, Patrich, and Reznick represent three of many theories proposing a location for the Temple - and at face value, among the most compelling. However, analyzed through the process of reconstruction, none of the theories are entirely viable or convincing. There is certainly a long history of associating the Rock with the Holy of Holies, as Ritmeyer does. However, descriptions of the Temple from Josephus and Middot indicate that the sanctuary was ten or more meters higher than the surface of the Temple Mount, while the top of the Rock is only 6.5 meters higher than the surface.

Of course, several subsequent structures were built on the same site, including a Roman temple and a Crusader church as well as two iterations of the Dome of the Rock. Over the course of all of these changes and almost 2000 years, it is certainly possible that part of the Rock’s elevation was removed. At the same time, the removal of four or more meters (the difference between its current height and the Holy of Holies) seems unlikely. In contrast, the difference in height between the current Rock and the altar would only have been about 1.5 meters – a much more realistic decrease in height. While Reznick’s rationale builds on some assumptions that have less documented evidence to support them (such as the beginning of a Messianic Temple under Bar Kokhbar), many other scholars consider the Rock to be a feasible site for the altar. The one aspect of Reznick’s proposal that seems highly improbable is the size and placement of the Antonia Fortress within the bounds of the Temple Mount. Reznick justifies his placement of the fortress by stating that Josephus described the Antonia as occupying half of the Temple Mount’s western wall (p. 150); Reznick also argues that the Antonia spanned the full width of the Temple Mount “for reasons too numerous and esoteric to elaborate upon” (p. 68). However, he acknowledges that this opinion differs from the majority of other scholars, most of whom assume the Antonia stood just outside the boundaries of the Temple Mount, aligned with the northwest corner.

Patrich’s approach is useful in that he does not begin with an assumption that the Rock must be part of the Second Temple. Cisterns were also certainly a pivotal part of Temple rites. However, the geometric layout resulting from Patrich’s hypothesis makes far less sense. Given that the Inner Temple likely matched prior Temple footprints, it is difficult to imagine a significant expansion of the Temple Mount where none of the walls aligned with the Inner Temple. It is even harder to imagine that an Inner Temple court would be trapezoidal rather than square – especially because the Court of the Women is described as having four square chambers in each of its four corners.

Ultimately, finding a satisfactory answer to the question of the Inner Temple’s location may require significantly more advanced tools for scanning subterranean archaeological remains, given that the Temple Mount continues to be a holy site and cannot be excavated.